Making the business case for prevention (and helping the historic Paris climate deal become a reality)

Decision-makers still need evidence if they are to prevent growing healthcare costs, including those relating to impacts from climate change. Daniel Black discusses systemic inertia and potentially transformative research projects.

- 27th January 2016

Decision-makers still need evidence if they are to prevent growing healthcare costs, including those relating to impacts from climate change. Daniel Black, Founding Director of research consultancy, Daniel Black and Associates (db+a), discusses systemic inertia and ends with several potentially transformative research projects that may provide decision-makers with the support they need. This is part of a series of blogs, where key players in Bristol’s health sector write about a health related subject of their choice. If you want to contribute, email [email protected].

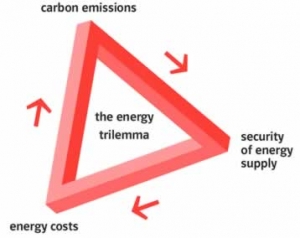

The ‘trilemma’

Human health is inextricably interlinked to all aspects of decision-making, whether it’s an individual choosing what to eat or how to move, or a government deciding what infrastructure to invest in.

Take the UK’s national energy strategy, which offers a perfect example of the systemic inertia facing the healthcare system. Sir Mark Walport, Government Chief Scientific Advisor and former long-term Director of the Wellcome Trust, gave a crystal clear summary of the UK’s energy needs at Bristol’s At-Bristol centre in December 2015.

The explicit message is that national government must seek to balance three things when considering energy supply: 1) security, 2) affordability, and 3) sustainability. It comes as no surprise that surveys show the electorate broadly supports tackling each of these vitally important areas within this ‘trilemma’.

That all sounds sensible…so what’s the problem?

The problem with this position is that it assumes parity of information between the three, when in practice there is an inherent and very significant imbalance. One can argue that there is no such thing as perfect information, but there is a very strong case to say that we know far more about short-term affordability of energy – and in all likelihood security too – than we do about long-term sustainability.

One obvious reason is that we can’t see into the future, where much of the concern about sustainability is directed. There is still no effective means of internalising into current decision-making the long-term ‘external’ costs that are increasingly being felt and are projected to get far more severe, such as impacts from extreme weather and a changing climate, or health impacts resulting from inequality, obesity and diabetes. Time and again long-term sustainability, though one of the three key areas of this energy ‘trilemma’, invariably loses out to the more immediate and tangible risks posed by energy security and affordability.

Short versus long-termism

Short versus long-termism

Those who’ve worked in sustainability and related areas will be familiar with the fallibility of the three-point visioning referred to by Sir Mark Walport.

The word ‘sustainability’ was enshrined nearly 30 years ago in the 1987  Brundtland Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development. Very soon after, the word on its own became meaningless as people interpreted it in their own ways, often with conflicting agendas and outcomes. For example, there is an irrefutable – but still hotly contested – conflict between patterns of economic growth based on short-term political cycles and increasing levels of consumption on the one hand, and longer-term environmental sustainability constrained by planetary boundaries on the other. This conflict lies still at the heart of our systemic inertia, and while it’s now widely recognised, there has been little real headway in overcoming this seemingly insurmountable obstacle.

Brundtland Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development. Very soon after, the word on its own became meaningless as people interpreted it in their own ways, often with conflicting agendas and outcomes. For example, there is an irrefutable – but still hotly contested – conflict between patterns of economic growth based on short-term political cycles and increasing levels of consumption on the one hand, and longer-term environmental sustainability constrained by planetary boundaries on the other. This conflict lies still at the heart of our systemic inertia, and while it’s now widely recognised, there has been little real headway in overcoming this seemingly insurmountable obstacle.

There are two statements relevant to the UK’s healthcare system, which illustrate this tension well. In 2010, the Department of Health stated that climate change could become ‘one of the greatest public health threats of the 21st Century’. While this year, the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney described climate change as “one of the biggest risks to (global) economic stability”, and said that “once climate change becomes a defining issue for financial stability, it may already be too late”.

So what can we do?

The historic deal made in Paris this month at COP21 – to radically decarbonise global consumption – shows us that global political leadership is possible. This, at long last, will start the slowly moving gears of the global regulatory systems. To use the ‘carrot and stick’ idiom, these are the ‘sticks’ we’ve been so badly in need of.

International and national policy and legal mechanisms will now be drawn up and enacted. It will affect public and private institutions around the world. It levels the playing field, which competing countries and private institutions so badly needed, and gives us hope that we might all be able to pull in the same direction rather than racing each other so tragically to the bottom. It also means that proactive public and private corporate entities that wish to lead in this area will be pushing at an open door. This is genuinely great news.

Are we saved then?

No. Not yet, at any rate. What’s more of a challenge is actually getting it done, and in time. Think of the complexity and the length of time it will take, not only to apply it, but also to monitor it in hundreds of different contexts around the world, not only where the personnel and infrastructure are not in place to administer this kind of bureaucratic, top-down reform, not to mention the fundamental inefficacies inherent to single-lever top-down legislative approach. And it’s a safe bet that countries will be looking over each other’s shoulders to make sure no one is cheating, so monitoring and evaluation will take time.

There’s a long way to go before we’ll know if progress is being made, and in the meantime the impacts from extreme weather, climate change and ill-health will continue to mount up. Even if we stopped all emissions today, the existing carbon in the atmosphere would continue to warm the planet for around 40 years (until it stabilises at that higher temperature). Given recent flooding in the UK and the much greater potential threat from overheating, not to mention the recent severe cuts in public sector services, that doesn’t bode well for the next few decades. That’s not to say there is no reason for optimism. Think how quickly the motorcar dominated our means of travel across the planet. If this climate deal can create the right conditions, then humans are sufficiently resourceful to respond.

Yet regulation forms only one part of a broad range of actions that create these conditions. The greatest challenge we are going to face – and this goes back to the problem of the trilemma – is changing the way we make decisions, and specifically how we place value on short and long-term outcomes, which no one yet in power appears to be addressing in any meaningful way.

Value versus politics

At the start of their tenure back in 2010, the current government bravely introduced a new national measure of wellbeing, but while it’s still ticking over in the background at the Office for National Statistics, it doesn’t appear to be a vote-winner. Despite some fanfare at the beginning, politically it appears to have sunk without trace.

The position taken by US Presidential Candidate, Hilary Clinton, following the Paris COP21 climate talks is far more reflective of modern-day politics: she tweeted that the deal clearly demonstrates that it is still possible to have business as usual while also protecting our planet: a clear vote-winner as it promises short and long-term gain with no sacrifice for the electorate (and no need, politically, to worry about whether the long-term argument is right or not).

As revealed obliquely by Sir Mark Walport in the keynote speech mentioned above, national government requires a mandate from the electorate if it is to rebalance the weight given to each of the three areas within the ‘trilemma’ to account more fully for longer-term impacts. This appears unlikely without a far more ‘eco-literate’ or ‘health-literate’ electorate. Yet Mark Carney’s statement is a clear admission that our current value mechanisms are not fit for purpose: “once climate change becomes a defining issue for financial stability, it may already be too late”. Either Hilary knows something we don’t, or many of our senior global leaders are missing a trick.

What’s the trick?

The trick is to overhaul our value and reward systems, which have become heavily out of balance and weighted towards short-term gain, and align public and private corporate interest to long-term health outcomes. This is easier said that done, but surely not beyond the wit of man.

Over the last few centuries we have invested a significant amount of resource into generating evidence about things we can measure easily as that seemed to lead to greater benefit, such as salaries, balance of payments, mortality rates, cost of healthcare. It’s only over the last half century or so that we are beginning to understand the no less important, longer-term cost-benefits. Now, with stronger and stronger data emerging, and with developments in new models of valuation and more intelligent discussions using qualitative as well as quantitative evidence, decision-makers can make better assessments of future risk and reward.

To use another example relevant to UK healthcare, let’s take disposal of public land. Most public sector landowners, including the NHS, dispose of their assets to gain the greatest possible capital receipt in order to pay for essential services in the short term. This makes complete sense from the point of view of the property or land surveyor whose role it is to maximise income from sale of property. However, when you take a step back and look at the provision of healthcare as a whole, and the clear policy from central government on the need for prevention, this isolated action fails spectacularly to achieve the overall purpose of the healthcare service.

Many landowners, public and private, fail to realise the amount of control they can exercise on the quality of development that comes forward. If we liken the development of land to the making of a film, the landowner is the executive producer. By giving up control of the development of that land, they also relinquish any control over long-term health outcomes. Typically, they will pass the property over to contractors who have no responsibility for long-term health outcomes. Unsurprisingly, the developments that come forward fail to prevent future health costs as they are not able to maximise healthy lifestyles: access to walking, cycling, healthy food, public transport is poor, low carbon energy sources are rare. On a small site-by-site basis, this may not amount to much, but this happens across the board, and when all these individual actions are scaled up, the cost to our society becomes very significant.

The challenge therefore is for society at large, and particularly those with most influence in the public and private sectors, to maximise both short and long-term gains by making sensible decisions about what our collective priorities are. In order to do that, we need to understand what those longer-term gains might be and then work out how to factor them in to current decision-making.

And how do we do that?

We already have the ability to value these external costs at a ‘global’ level. For example, a report by US-based consultancy, McKinsey & Co, estimated recently that the annual healthcare cost to the NHS for treating people with obesity was around £47 billion pounds; the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development has estimated that their members would be willing to pay $1.7 trillion to prevent the 3.2 million annual deaths from air pollution; while the cost of global biodiversity decline by 2050 has been estimated at £14 trillion. These valuations are not meant to be exact. Instead, they provide useful ‘ball park’ estimations of the scale of the problem to help steer national and international policy. However, as they are based on myriad assumptions and do not align to specific individual organisation interests – the tragedy of the commons – they tend to be trumped by short-term value judgments, often politically or economically driven.

Beyond sensible discussions about risk and reward, and a critically important wider discussion looking at systemic blockages, making these ‘global’ costs relevant to individual organisations – public and private – offers a potentially significant and immediately impactful part of the solution. The feasibility of this approach underpins the three research projects we are involved in, one of which we are carrying out in partnership with Bristol Health Partners.

Launched in October 2015 and running for a year, the aim of this feasibility study is two-fold: firstly, we are seeking to estimate how much Bristol‘s healthcare providers might have to pay (or how much money they might lose) as a result of impacts from extreme weather events: flooding and overheating in particular; and secondly, to explore with stakeholders what the organisations can do to minimise these potential costs. One of the real challenges is the need to engage at both the local and the national level. A useful example of relatively simple local level impact is the recent flooding in Cumbria, where flooding of electricity sub-stations resulted in the closure of multiple health services.

This is one of two projects co-funded by InnovateUK, a government-funded agency that invests £400m each year in innovative products and services to grow the UK economy, and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). Partners on this project are the Universities of Bath and Bristol, and with support from the Global Climate Adaptation Partnership.

Partners on the other project, which looks at the social housing sector, include the University of Manchester and Aster Group. These projects are feeding in to a three year pilot project funded by the Wellcome Trust looking at the links between urbanisation and health. More details of these projects can be found on the Daniel Black and Associates (db+a) website.

Daniel Black is also Director of multi-award-winning low carbon development, Clipper Estates, and Visiting Research Fellow at the University West of England.